Aurora’s ‘Three Strikes’ Law Sees 1000 Cars Impounded, Dozens Auctioned

Aurora’s controversial “Three Strikes” traffic law has led to the impoundment of 1000 vehicles between November and February, with at least 38 of those vehicles sold at city-run auctions. The ordinance, introduced by Councilmember Stephanie Hancock, mandates that police tow and impound any vehicle if the driver is caught without a license, proof of insurance, and valid registration. The law aims to crack down on a surge in expired, fake, or missing license plates—an issue Aurora officials say has grown since the pandemic.

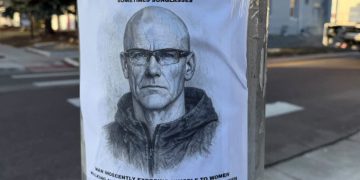

Despite its safety intentions, the policy has faced criticism for disproportionately affecting low-income residents who may struggle to afford registration, insurance, or fines. Opponents on the city council say the policy veers more punitive than productive, especially as impound fees and court costs can quickly escalate into thousands of dollars. Aurora Police Chief Todd Chamberlain shared that the department has mapped out areas with the highest number of violations, highlighting hotspots on East Colfax Avenue and Havana Street. Data also revealed that nearly a third of the impounded cars had no record of ever being legally registered.

Currently, Aurora doesn’t financially benefit from the citations, as all cases are processed through county court, directing revenue to the state. A bill moving through the Colorado Legislature, House Bill 1112, could change that by allowing municipalities like Aurora to prosecute registration violations locally. The bill has bipartisan support, with Hancock collaborating with Democratic lawmakers to push for local authority over these infractions.

Meanwhile, city records show the average auction price of impounded vehicles hovers around $791, with some selling for as much as $2,700. Others, particularly those with no bids, go unsold. Aurora residents face impound release fees starting at $400, plus daily storage and towing costs. For those who can’t afford to reclaim their vehicles, the auction becomes a last resort.

Though Hancock defends the law as a way to restore accountability on the roads, critics say its enforcement under a statewide consent decree—triggered by findings of racial bias in the Aurora Police Department—demands careful scrutiny. Still, nearby cities like Colorado Springs and El Paso County are reportedly watching closely as they consider implementing similar enforcement models.